Chagos lies 300 miles south of the southernmost island of the Maldives, a 500 mile long chain of atolls, which has been long known to the Arab traders who crisscrossed the Northern Indian for thousands of years, but Chagos lies outside those traditional tradewind routes. Ptolemy's Geography (circa 150 AD), the first written reference to the central Indian Ocean archipelagoes, identifies the islands of the Maldives, but made no reference to the islands that are now known as Chagos. It wasn't until the Portuguese explorer Vasco de Gama sited these islands in 1532 that the islands of Chagos became known to the world. But unlike the atolls of the Maldives, which were settled centuries ago by waves of immigrants from India and Sri Lanka, the Portuguese found the islands of Chagos to be uninhabited. As they weren't suitable for growing spices or as a source of slaves, the islands of Chagos remained unmolested for two more centuries.

During the 1700's, the Portuguese monopoly in the Indian Ocean was broken up by the Dutch, English and French, who were all scrambling to claim an island or two of their own. While the Dutch were preoccupied by their bid to control the trade routes around Indonesia, the Malacca Strait, and Sri Lanka and the English were busy mapping the east coast of that sunburned continent now known as Australia, the French did quite well for themselves, claiming Mauritius, the Seychelles and Reunion. In 1776, with the English distracted by a spot of trouble in their American colonies, a French ship sailed up from Mauritius to Chagos to plant a flag and claim these islands for Napoleon. Wasting no time, a French fishing company applied for and was granted a land concession. In exchange for accepting leprosy sufferers from Mauritius, the French company was granted the right to "enjoy the facilities of the islands."

For the next few decades, the French imported lepers into Chagos while they exported coconuts, turtles, sea birds and fish. After the defeat of Napoleon in 1814, the Treaty of Paris transferred ownership of Mauritius, and its dependency Chagos, from France to England. Under British rule, the coconut industry in Chagos grew and additional workers were brought in from Mozambique, Madagascar, the Seychelles, and India. By 1900, there were approximately 426 families living in Chagos.

1893 headstone in the cemetery on Ile du Coin

In the 1950's, the British Colonial Office shot a film in Chagos, in which the narrator extolled the beauty of the islands and stated that they were inhabited "mostly by men and women born and brought up in the islands." The population of Chagos, which was originally primarily male, evolved over the generations into a matriarchal society as female leprosy sufferers lived longer than males. Over time, the islanders developed a Creole dialect that few outsiders could understand. The islanders kept pigs, chickens, ducks and dogs. Their homes were surrounded by gardens in which they grew eggplants and cucumbers. Their primary religion was Catholic. By the 1950's, many of the 1,800 people living in these islands had never known another home. Their parents or grandparents might have come from Mauritius or the Seychelles, but Chagos was their home. Unfortunately for them, there home had become valuable real estate.

The interior of the church on Boddam 1975, two years after the deportation of the last of the islanders

During World War II, the British established a military base on Gan, an island in the southernmost of the Maldivian atolls. In 1956, when they had to pull out of Sri Lanka, the British expanded their presence on Gan into a Royal Air Force Base. The benefits of having a base in the Indian Ocean from which Soviet activities could be monitored were not lost on the folks working at the U.S. Pentagon during the height of the Cold War.

The exterior of the church on Boddam today. The roof and most of the windows are long gone. Trees grow inside where statutes used to reside.

In 1965, the British granted Mauritius its independence, but as part of the deal they insisted that Chagos be portioned off to become part of the British Indian Ocean Territory ("BIOT"). For a time, BIOT would also include several islands to the north of Madagascar that are now part of the Seychelles. The following year, the British leased BIOT to the United States for 50 years with an option to renew. The only apparent fly in the ointment was that the Americans insisted on leasing an unpopulated archipelago to ensure maximum security for the base. So what was to become of the 1,800 residents of Chagos?

Over the next decade a series of agreements were reached between the British and the United States that turned Diego Garcia, the largest atoll in Chagos, into an American military base. During the same time period, the islands were depopulated. Islanders who traveled to Mauritius to visit relatives and buy supplies for their families on Chagos were not permitted to return. BIOT purchased the company that ran the coconut plantations, and proceeded to shut them down. Imports of rice were cut off. By taking away the islanders' jobs and restricting their food supplies, BIOT encouraged approximately 1,000 islanders to leave Chagos between 1965 and 1971. By 1971, when the first Americans arrived in Diego, BIOT could claim that there were only 830 islanders in the archipelago.

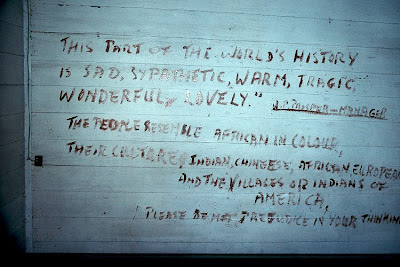

Writing on the wall of the anager's house on Ile du Coin

When the Americans arrived in Diego, the remaining islanders were removed to Salomon and Peros Banhos atolls, which are over 100 miles to the north of Diego. But that was still too close to the U.S. base, so in 1973, BIOT evacuated the remaining islanders to Mauritius. The tragic experiences of the Chagos exiles in Mauritius, their attempts to return to Chagos, and the disposition of the case that they brought before the British High Court in London, is all beyond the scope of this post. But suffice it to say that Diego Garcia has become one of the most strategically important American military bases in the world. It is home to U.S. military personnel, merchant mariners, and BIOT officials and support staff. Its isolation enables it to be extremely secure. It is unlikely that the Americans will fail to renew their lease, or that they will permit the Chagos exiles or their descendants to return to Diego or the outlying atolls. And so, churches fall into ruin, cemeteries become overgrown, and coconut crabs and birds reclaim islands that humans inhabited for a brief 200 years.

In 2005 the manager's son returned to Ile du Coin and left his mark on the wall of the house in which he was born.

2 comments:

You may have been influenced the recently published "Island of Shame" by David Vine. Vine's research is excellent. But he starts with the premise of proving US imperialism by using the Chagossians as a case study. He intentionally confuses the forced evacuation of Diego Garcia with that of Peros Banhos and Salomon Atolls, and then takes statements out of context or draws incorrect conclusions to prove his point. He stated last week,

"The British would dearly like to make amends, but the almighty USA is immune to the sentiment." While such statements will be popular in the international peace movement, they are not based on reality. The UK created this problem and the UK can bring justice to the people of the Chagos Archipelago.

Responsible authorities on the politics of the situation as it is today believe that the Americans don't really care if the northern atolls are resettled, as long as the area is controlled by the UK, not the Chinese, the Taliban or the North Koreans.

The resettlement of the northern atolls has become a moral issue rather than a legal one, considerable pressure is coming from the new Chagos All Party Parliamentary Group and the Tories seem favourably inclined toward a just solution. Perhaps New Labour will deprive them of this by doing the right thing before next year's election.

I wonder who would "support" the Chagossians should they be allowed to return? Those islands are so remote and copra is no longer the commodity it used to be in the days the plantations were active. Other than seafood, coconuts and water, nearly everything else needed to sustain a population must be shipped or flown in. It is truly a pipe dream to be able to return to those islands and inhabit them without a massive supply network to ensure survival. Economically this is nearly impossible as it would be literally be a money pit. Dreams of vacationers and tourists flocking there are just that....dreams. To build even the most basic of accommodations would be daunting on the outer islands. Supporting and maintaining the infrastructure already present on Diego Garcia, assuming the U.S. and U.K. would cede the island to the Chagossians, would be prohibitively expensive. Just the facts, folks!

Post a Comment